Former Atheist William Murray, Son of the Founder of American Atheists, Converts to Christianity.

Bishop's Encyclopedia of Religion, Society and Philosophy

Now deceased Madalyn, once known as the most hated woman in America and a title she apparently took great pleasure in (1), fought a war against school prayer and won. It was further ruled in her favour that official Bible-reading in American public schools in 1963 and onward would cease. According to her son Murray (now 70 years of age), as captured on film while still a school pupil during this whole affair, “I am an atheist, and I wish to be an atheist, and I don’t feel it would be appropriate for me to stand up and say the Lord’s Prayer” (2). Madalyn subsequently founded the American Atheists and sued the city of Baltimore demanding that the state collected taxes from the tax exempt Catholic church. She also sued NASA arguing that public prayer ought to be banned by government employees in outer space. She would also…

View original post 1,080 more words

Nicole Oresme’s “De origine, natura, jure et mutationibus monetarum”

An old article, but it’s nice to see the good bishop get some airtime.

Nicole Oresme (1320 – 1382)

Nicole Oresme is a scholastic from the 14th century. He is not quite the theologian and philosopher that Aquinas was, but he may be considered the greatest economist of the Middle Ages. He is credited with writing one of the first treatises on economics, which turns out also to be the first treatise on money. Oresme was born near the city of Caen in Normandy. From about 1341, he resided at the University of Paris. He left the university in 1362 to serve Charles V for whom he translated the works of Aristotle from Latin into French.

De origine, natura, jure et mutationibus monetarum (The Treatise on the Origin, Nature, Law and Alternations of Money). It is unclear when Oresme wrote his treatise, but it seems he wrote the original latin text and a french translation (Traictié de la premiere invention des monnoies) before leaving the University…

View original post 307 more words

Remember Merdeka.

In 1967 the president of Philippines Diosdado Macapagal authorized what would become known as “Operation Merdeka”. It was a codename for a destabilization program where the end goal was the annexation of Sabah, a resourceful region in north-east Malaysia.

View original post 2,403 more words

American vampires in… The Philippines?

We all have our heroes to aspire too. It’s an important way to motivate ourselves and set goals we can all pursue. And while I have no doubt that the average gun-totting Joe Jar-head dreams o…

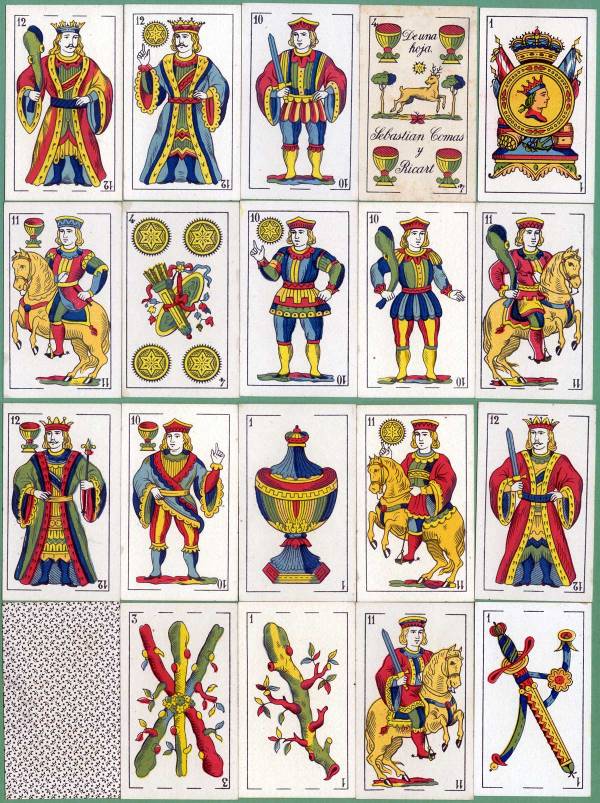

Clarifying a misconception on the definition of “Filipino”

How timely it surely is that, as we celebrate History Month, two individuals who are very passionate in the study of Filipino History introduced a new argument that the long-accepted historical definition of the term Filipino, i.e., Peninsular Spaniards who were born in Filipinas, is dead wrong. In a Tagálog article written by Mr. Jon Royeca on his blog last August 14, he argues that the claim made by previous historians, particularly Renato Constantino, that the Insulares were the first Filipinos was wrong. He went on and cited Fr. Pedro Chirino’s monumental work Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604) as his source:

Heto ang katotohanan… tinawag ng may-akda niyon na si Padre Pedro Chirino ang mga Tagalog, Bisaya, Ita, at iba pang katutubo ng Pilipinas na Filipino.

(Here’s the truth… the author, Father Pedro Chirino, called Tagálogs, Visayans, Aetas, and other natives of the Philippines as Filipino.)

Royeca then shared his blogpost…

View original post 1,358 more words

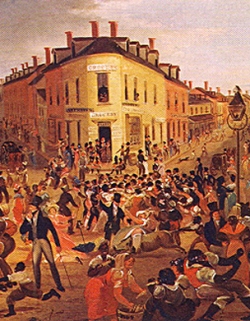

Origins of the police

I wonder what the origins of the police are in the Hispanic world?

The Five Points district of lower Manhattan, painted by George Catlin in 1827. New York’s first free Black settlement, Five Points was also a destination for Irish immigrants and a focal point for the stormy collective life of the new working class. Cops were invented to gain control over neighborhoods and populations like this.

The Five Points district of lower Manhattan, painted by George Catlin in 1827. New York’s first free Black settlement, Five Points was also a destination for Irish immigrants and a focal point for the stormy collective life of the new working class. Cops were invented to gain control over neighborhoods and populations like this.

In England and the United States, the police were invented within the space of just a few decades—roughly from 1825 to 1855.

The new institution was not a response to an increase in crime, and it really didn’t lead to new methods for dealing with crime. The most common way for authorities to solve a crime, before and since the invention of police, has been for someone to tell them who did it.

Besides, crime has to do with the acts of individuals, and the ruling elites who invented the police were responding to challenges posed by collective…

View original post 7,122 more words

2014 in review

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2014 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

A San Francisco cable car holds 60 people. This blog was viewed about 1,500 times in 2014. If it were a cable car, it would take about 25 trips to carry that many people.

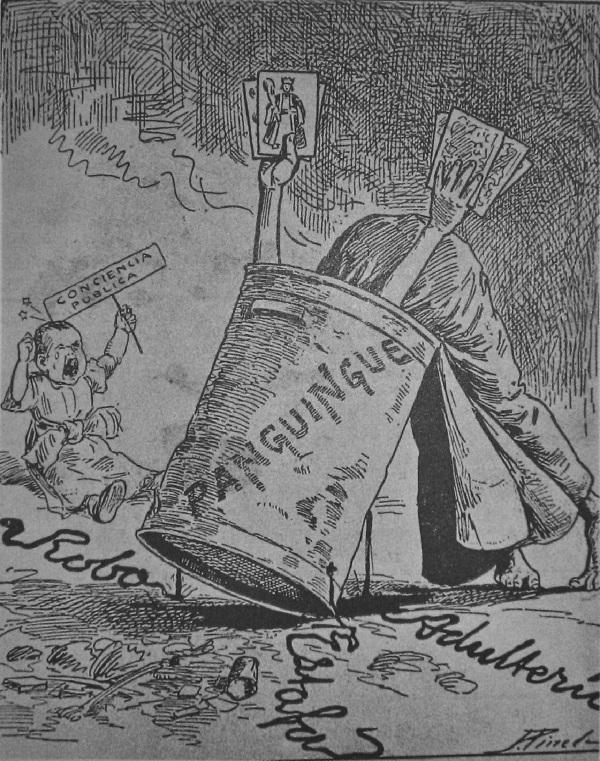

Statolatry I: José Rizal is your god and your god hates chickens

There are two concepts which describe an action, used (or at least should be used) in the construction of the laws:

malum in se (Latin: evil in itself; pl. mala in se) and

malum prohibitum (Latin: evil, because it is prohibited; pl. mala prohibita).

Filipinos have been mixing up these two concepts for the longest time. This state of confusion is generally a result of étatism (French: statolatry), the idea that the glorification and aggrandizement of the “Philippine government” or the “Filipino Nation” is the object of all legitimate human aspiration at the expense of all else, including personal welfare and independent thought.

(TL;DR version: Everything the government says should be followed. Ignore useless concepts such as good and evil. Only what is lawful or unlawful as determined by the state matters. Anyone saying different, like people following the dictates of their conscience or religion, are troublemakers.)

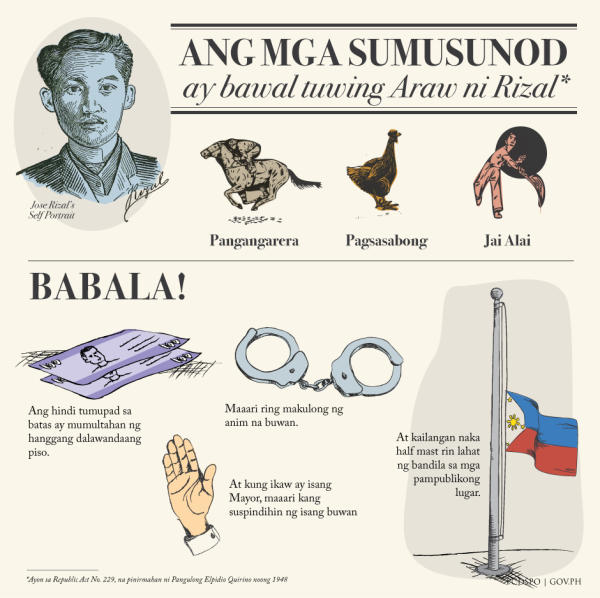

On 29 December 2014, the Malacañang Palace Facebook page posted this delightful infographic, once more reminding Filipinos that, not only was José Rizal a sainted political messiah who must be given due veneration, but any challenge to this reality will be met with force by the state.

«Ang̃ mg̃a sumusunod ay báual tuwing Arao ni Rizal» (The following actions are prohibited on Rizal’s Day)

First, take a look at the law mentioned (See: RA 229). The full name of the law is «An act prohibiting cockfighting, horse racing and jai-alai on the thirtieth day of December of each year and to create a committee to take charge of the proper celebration of Rizal day in every municipality and chartered city, and for other purposes.»

Just the title alone reveals the condescension the state feels for its citizens. The assumptions behind this act are:

- What a Filipino does in his free time is not up to him. The state will tell him what to do.

- Filipinos are ignorant of the “martyrdom” of José Rizal whose apotheosis from mere mortal to national hero reflects the divine majesty of the Philippine government. (N.B.: Last time I checked, martyrdom involves voluntarily choosing death for a higher purpose. Rizal was shot by the government only because Bonifacio name-dropped him on just about every KKK document he could write on.)

- Filipinos do not have the mental capacity to observe this civil holiday without state intervention.

- Certain hobbies, lawful on the other 364 days of the year, are incompatible with the holiness of 30 December and are for the next 24 hours to be considered evil.

- Politicians nationwide now have another bureaucracy with which to fill with relatives and gorge from the collected taxes of people.

All this, and I haven’t even gotten to the body of the document!

¿Notice the dire pronouncements that will befall all who disregard the entitlement of the state to intervene in their private lives?

As per §3 of RA 229:

Any person who shall violate the provisions of this Act or permit or allow the violation thereof, shall be punished by a fine of not exceeding two hundred pesos or by imprisonment not exceeding six months, or both, at the discretion of the court.

Imagine that… Six months incarceration. This is the same penalty for:

- Not filling out a census form correctly (CA 591);

- Killing a carabao or a horse without the blessing of the Secretary of Agriculture and Commerce (RA 11);

- Selling tobacco overseas (RA 31);

- Possession of “deadly arrows” (RA 3553);

- Illegal logging (RA 3701);

- Electronic surveillance without a warrant (RA 4200);

- Possession and use of prohibited drugs (RA 6425);

While some may recoil at the thought of incurring arresto mayor for violating this law, most Filipinos dismiss the monetary penalties that accompany RA 229. However, at the time the law was promulgated (9 June 1948), the peso was still legally defined as 12.9 grains of gold 0.900 fine (0.026875 XAU) by the 3 March 1903 Philippine Coinage Act.

(N.B.: It would still be a year before the opening of the Central Bank of the Philippines and the massive estafa by the Philippine government that robbed an entire nation of their savings in gold and silver, replacing it with an ever-depreciationg fiat currency, the modern Pilipine peso.)

Using the 30 December 2014 gold-peso (XAU/PHP) exchange rate of 1 troy ounce of gold = ₱53,973.04, this would mean that an offender in 1948, would be facing a fine equivalent to 5.375 troy ounces of gold or ₱290,105.09 in today’s money. A very hefty sum for any inhabitant who has just survived the Greater East-Asia War. The heavy hand of the state cannot be made much more clear. Be patriotic… or else!

Let us compare Republic Act No. 229 to the original 20 December 1898 decree establishing a day of national mourning:

| GOBIERNO REVOLUCIONARIO | REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNMENT |

|

DE FILIPINAS |

OF THE PHILIPPINES |

|

Decreto |

Decree |

|

SR. EMILIO AGUINALDO Y FAMY, |

MR. EMILIO AGUINALDO AND FAMY, |

|

PRESIDENTE DEL GOBIERNO REVOLUCIONARIO DE FILIPINAS, |

PRESIDENT OF THE PHILIPPINE REVOLUTIONARY GOVERNMENT, |

| CAPITAN GENERAL Y GENERAL EN JEFE DE SU EJERCITO. |

CAPTAIN GENERAL AND COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF OF THE ARMY. |

| Atendiendo á las aspiraciones dcl pueblo Filipino, é interpretando sus sentimientos nobles y patrióticos vengo en decretar lo siguiente: | Heeding the desires of the Filipino people to express their noble and patriotic feelings, I decree the following: |

| Artículo 1º En memoria de los grandes patriotas filipinos Dr. José Rizal y demás víctimas que sucumbieron bajo la extinguida dominación española se declara día de luto nacional el día 30 de Diciembre. | Article 1. In memory of the great Filipino patriot Dr. Jose Rizal and other victims who died under the previous Spanish government, a national day of mourning day is declared on December 30. |

| Art. 2º Con tal motivo desde el medio día, del 29 hasta el medio día del 30 en señal de duelo se izará á media esta la bandera nacional. | Art. 2. For this reason, the national banner shall be flown at half-mast as a sign of mourning from noon the 29th until noon the following day. |

| Art. 3º Vacarán todas las dependencias del Gobierno Revolucionario durante el día 30 de Diciembre. | Art. 3. All government functions of the revolutionary government shall be closed on December 30. |

| Comuníquese y publiquese para general conocimiento. | Communicated and published for general distribution. |

|

Dado en Malolos á 20 de Diciembre de 1898. |

Given in Malolos on 20 December 1898. |

|

El Presidente, —EMILIO AGUINALDO |

The President, —EMILIO AGUINALDO |

¿Notice the difference in tone?

- Apparently, many people, other than Rizal, were executed unjustly by the Spanish government.

- Those people deserve recognition too, not just one man, no matter how high in esteem he was held.

- This decree was written at the request of the Filipino people, not imposed from on high.

- The government, acting as a representative of the people, indicate their mourning by lowering the flag. No more, no less.

- All government offices are closed so that those in the public service can be with their loved ones, either at home or at the cemeteries.

- Being Commander-In-Chief of the Army doesn’t grant the President the right to command civilians.

- There are no injunctions to prevent people from doing anything on 30 December and certainly no six-figure fines for breaking such injunctions.

Perhaps we need to question why Filipinos are so accepting of such petty tyrannies coming from Malacañang.

The Founding of Manila and the Origin of Global Trade, 1571

Ancient history or current events?

In 1995, historians Dennis O. Flynn and Arturo Girldez published a seminal article in the Journal of World History entitled “Born with a ‘Silver Spoon’: The Origin of World Trade in 1571.”

Global trade emerged with the founding of Manila in 1571, at which time all important populated continents began to exchange products continuously. The silver market was key to this process. China became the dominant buyer because both its fiscal and monetary systems had converted to a silver standard; the value of silver in China surged to double its worth in the rest of the world. Microeconomic analysis leads to startling conclusions. Both Tokugawa Japan and the Spanish empire were financed by mining profits–profits that would not have existed in the absence of end-customer China. Europeans were physically present in early modern Asia, but the economic impact of China on Western lands was far greater than any…

View original post 12 more words